I’m not a native plant purist (I ache for a tea cup magnolia) but still I recommend native substitutions for the imported nursery standards nine times out of ten. It just makes sense on so many levels:

-

Birds, bees, and wildlife in general have coevolved with their native flora. That means they rely on the specific nutrition and timing of their native plant’s blooms and fruits. Spicebush Swallowtail Butterflies only lay eggs on Spicebush and Sassafras - two native members of our understory. Our native Oak trees host 2,300 species of wildlife!

-

Imported plants that have no natural predators can easily out compete slower growing native plants. Maybe you plant a beautiful Japanese Barberry in your garden and think that it’s not really hurting anyone. Birds will eat that berry and the spread the seed in nearby wild spaces and within a few seasons, the entire understory of a nearby wild space can be overtaken by Barberry, thereby wiping out the diversity of plants, mushrooms, and wild life that were thriving there before. No more Spicebush or Sassafras in the understory. No more Spicebush Swallowtail Butterfly.

-

Native plants are better suited to your environment so they will likely look happier and healthier with minimal intervention from you. Of course, you still have to consider soil and sun preferences, but that is the bare minimum. When I go to my mom’s garden and see the Shrubby Saint John’s Wort and Great Blue Lobelia I started from seed thriving in her garden it makes me so happy :)

I think it is helpful to reframe how we see our gardens: they can be both places that we go to collect food medicines, and flowers, as well as expressions of our aesthetic tastes, and also part of our local ecosystem. The choices we make in our gardens, from planting non-native plants that add little to no value to the ecosystem to spraying round up, effect the ecosystems around us more than we’ll ever see. Just as planting vigorous invasive plants can have disastrous effects on the diversity and resilience of your ecosystem - planting native plants can have an incredibly supportive and life giving effect.

It’s worth mentioning that not all imported plants are invasive or bad. Some species do not spread aggressively or compete with native species and even provide food for pollinators. I consider these plants “naturalized” and I would count many of the vegetables and herbs in our garden in this category: kale, calendula, tulsi, and chamomile to name a few. That said, when given the chance - choosing the native variety adds even more value to the garden and ecosystem than plants that may be neutral in their effect.

Hayden and I are nearing the end of our time in New Haven and I was remarking to him the other day that as soon as we get back on the land, I want to plant a patch of asparagus. He said “Okay, but why not plant Solomon’s Seal instead? That way you can harvest the delicious young shoots and eat them like asparagus but you are also growing a threatened native plant that you would be able to make medicine from as well?” Love him.

Today I have chosen to highlight our native Angelica. Sure, you could grow the European Angelica archangelica and it would be a fine addition to your garden without any danger of out competing native species. But when you grow the native Angelica atropurpurea it is actually additive to your ecosystem.

Angelica atropurpurea,

Apiaceae (the carrot family)

Energetics: warming, stimulating

Taste: bitter, aromatic, sweet

Harvest: roots in the autumn of the first year or spring of the second year

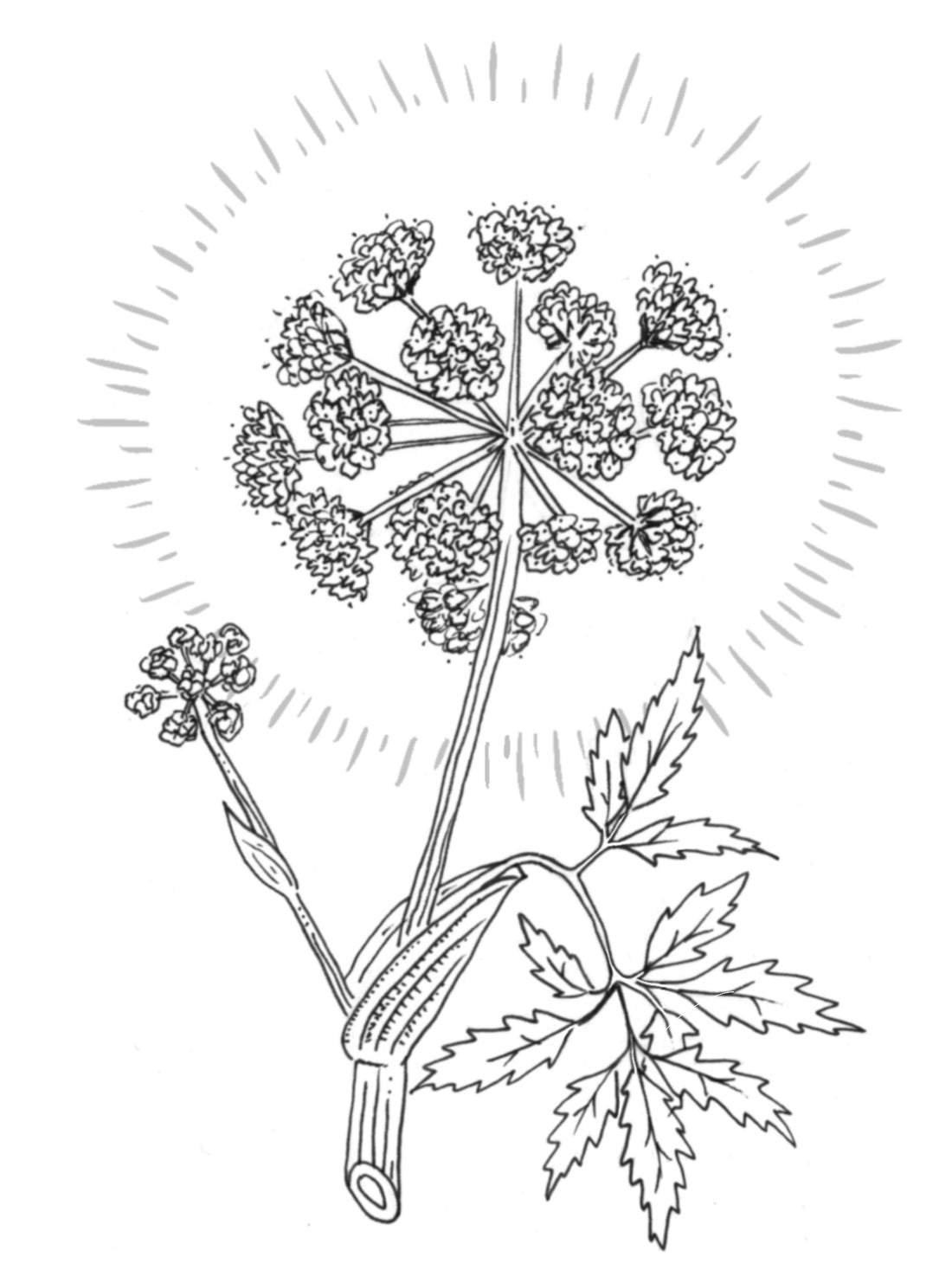

Angelica atropurpurea is native to North America and can be substituted for the European species, Angelica archangelica, which is more commonly referenced and found in commerce. Angelica is a biennial, meaning it takes 2 full growing seasons to complete its life cycle. In the first year, Angelica establishes a taproot and forms a lush rosette of basal leaves. In the second year, Angelica sends a smooth, purple stalk into the sky, sometimes greater than six feet tall with globes of enchanting umbel shaped flowers. Most often I encounter Angelica growing along stream beds, near ponds and in the wetlands.

Angelica is associated with the lungs, the digestive system, and the female reproductive system. Angelica warms and stimulates a cold and stagnant state. In the lungs, Angelica acts as an expectorant and can be taken as a hot decoction 3 times a day to break up a cold, especially one with a fever. Angelica is a good choice for a digestive bitters formula when food seems to be sitting heavy in the stomach and gas is severe. For the female reproduce system, Angelica can behave as an emmenagogue, gently encouraging the period’s arrival. This passage from one of my teachers, Matthew Wood, explains Angelica’s influence on the female reproductive system beautifully:

“Angelica was not originally used as a female medicine in our tradition, like its Chinese cousin Angelica sinensis (Dong Quai). It does not possess the estrogenic compounds of the latter. However, by increasing digestion, assimilation, and fat metabolism, while decreasing blood stagnation, it would pretty much have the same effects.” - The Practice of Traditional Western Herbalism, pg 244.

Angelica is a solar herb, ruled by the sun and energetically inclined to offer gentle warmth and drying up of murky waters. Besides taking Angelica internally, the root can be dried and worn around the neck for protection or burned to experience the spirit medicine of this plant.

Medicine Making:

Tincture: fresh root (1:2, 95% alcohol); dried root (1:5, 65% alcohol). Standard dosage: 1-3 ml up to 3 times daily.

Decoction: 1/2 cup, up to 3 times daily. For instructions on how to make a decoction, click here.

Warnings: Not for use during pregnancy. DO NOT MISTAKE FOR WATER HEMLOCK! Water Hemlock is another native plant in the same botanical family that grows in similar habitat and looks vaguely similar. However it is poisonous and potentially fatal. So, if you are foraging native Angelica, please do everything you can to ensure you have a correct ID. Feel free to send me photos.